Bridging the Gap: An Exploration of the Hidden Factors Behind Minority Health Inequalities

Bridging the Gap: An Exploration of the Hidden Factors Behind Minority Health Inequalities

Abeni Smith

Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology

This article placed 1st in the 2024 Teknos Fall Writing Contest.

Health disparities refer to the significant inequalities in health outcomes between certain demographics [2]. Population health scientists suspect that these differences are not determined by any inherent genetic characteristic, but rather by an individual's surrounding environment, prompting the term ‘Social Determinants of Health’ [8]. They argue that such determinants—such as differences in socioeconomic status, employment, education opportunities, and other resource inequalities—have the power to either negatively or positively affect the health of the residents. Recent research confirms that ethnicity and race also play a role in health outcomes, as it not only reinforces the effects of one’s Social Determinants of Health, but also creates new barriers [2].

To quantify the intersection between ethnicity, environment, and health, White et al. created a ‘county-level structural racism index’ for 134 counties in Georgia [3]. They used factors such as the history of residential segregation, incarceration rates, and education quality obtained from the American Community Survey to determine to what degree systemic racism exists in these counties. They cross-referenced this data with air toxin data across Georgia from the US Environmental Protection Agency, focusing heavily on traffic-related carcinogens. Counties with structural racism indexes above the 75th percentile had a roughly 7.8 times higher risk of developing cancer. Counties with higher indexes tended to have a lower socioeconomic status and provided limited education and job resources. Therefore, residents neither had the resources to improve their home county nor relocate to a better environment. By confirming the correlation between race and class, White et al. revealed that the residents of these polluted counties were—in every sense of the word—trapped [3].

In addition to the aforementioned impact, racial and ethnic minorities also face barriers to achieving quality healthcare at the institutional, rather than the community, level. For example, minority groups are widely underrepresented in clinical health trials. Clinical research is critical to expanding and formalizing our knowledge of how diseases and their treatments affect the human body. Without diverse patient populations, our current knowledge cannot be effectively applied to all groups of people [1].

According to the 2023 report from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG), one of the most underrepresented populations in clinical trials are children whose families speak a language other than English. To assess the factors behind this, Beauchemin et al. sent a twenty-question survey to 230 institutions associated with COG with the intent to catalog their translation and interpretation resources for patients, specifically regarding enlistment into clinical research trials [1]. Of the 139 institutions that responded, 47% of them reported it being either “somewhat difficult” or “very difficult” to obtain clinical research consent from patients. Additionally, half of the respondents reported “difficulty finding required resources” as a main barrier to obtaining consent. Beauchemin et al. suspected that this was due to a mismatch between the strict regulations surrounding obtaining consent, which were put in place to protect the boundaries of the patients, and the ability to access, afford, and comply with them [1]. For example, around half of Institutional Review Boards require their institutions to provide both fully translated consent forms and an in-person translator for one to participate in a clinical study, but 46% of institutions are unable to cover the cost of translation for their patients, 23% of institutions don’t have access to any in-house interpreters, and 12% of institutions prohibit the use of short-form consent forms combined with verbal translation as a stand-in for written consent. Ultimately, their research showed that to diversify patient groups and ensure that nonnative English speakers can receive equitable clinical research representation, the lack of appropriate resources needs to be rectified.

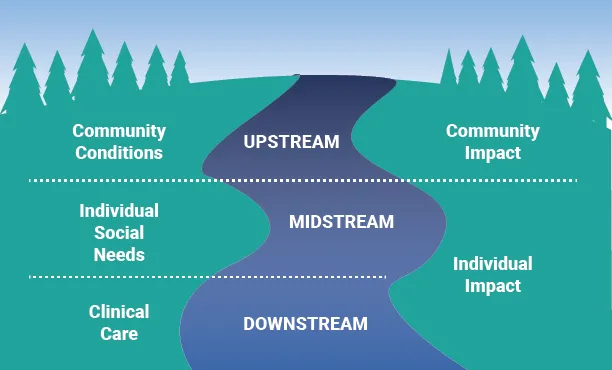

Some believe that the best way to achieve health equity is for the global network of healthcare to focus their work further ‘upstream’ (Figure 1) by addressing health disparities at the community level [6]. One example of this is the Peer Approaches to Lupus Self-Management (PALS) project [4]. This study tested the effects of peer-to-peer mentoring on African American women afflicted with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), a chronic autoimmune disorder that has disproportionately high susceptibility and severity rates within minority groups, particularly young African American women. Specifically, PALS researcher Dr. Sarfaraz Hasni cataloged the efficacy of the peer-to-peer approach in increasing the likelihood of enrollment in clinical trials. Currently, only 14% of SLE clinical trial participants are African American [4]. To establish this program, Hasni facilitated the training of current participants in SLE clinical studies and then matched these mentors with prospective participants. He discovered that 66% of research subjects felt more supported in peer interventions versus other approaches. In an interview, Hasni revealed his reasoning behind the peer-to-peer mentoring approach: racial biases prevent information flow from health providers to patients. Preliminary research revealed that physicians are not recommending their Black and Brown patients as clinical research participants at the same rates as their White patients and that this lack of trust is so ingrained into medical institutions that it is functionally impossible to account for this disparity [3]. However, the project supports the notion that moving the burden of education from ‘elite’ physicians to peer mentors restores that lost trust and allows room for a culturally sensitive approach [7].

Investigations such as those by Beauchemin et al. and White et al. that work to identify overlooked weaknesses in worldwide healthcare systems are equally important as controlled studies like PALS. However, the common thread between both categories is how they work to uplift the voices of minorities, or the “stakeholders” as Hasni phrased it in the following:

The stakeholders need to be given their seat at the table. We need to listen to what they think of as a challenge in terms of health inequality, health disparities, and not participating in clinical research (...). Sometimes [scientists] get so siloed in that we come up with these solutions and ideas, but if we don’t have the stakeholders involved we are just in this echo chamber [7].

This field of minority health and health disparities research has grown exponentially in recent decades [2]. As more professionals choose to focus their efforts on these social inequalities and as community voices are welcomed instead of shunned, the opportunity to turn experimental studies into real initiatives only grows.

References

[1] Beauchemin, M. P., Ortega, M., Santacroce, S. J., Robles, J. M., Ruiz, J., Hall, A. G., Kahn, J. M., Fu, C., Orjuela-Grimm, M., Hillyer, G. C., Solomon, S., Pelletier, W., Montiel-Esparza, R., Blazin, L. J., Kline, C., Seif, A. E., Aristizabal, P., Winestone, L. E., & Velez, M. C. (2024). Clinical trial recruitment of people who speak languages other than english: A children's oncology group report. JNCI Cancer Spectrum, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pkae047

[2] Collyer, T. A., & Smith, K. E. (2020). An atlas of health inequalities and health disparities research: "How is this all getting done in silos, and why?" Social Science & Medicine, 264, 113330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113330

[3] Coy, T., Brinza, E., DeLozier, S., Gornik, H. L., Webel, A. R., Longenecker, C. T., & White Solaru, K. T. (2023). Black men's awareness of peripheral artery disease and acceptability of screening in barbershops: A qualitative analysis. BMC Public Health, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14648-x

[4] Hasni, S. (2021, March 19). Increased minority participation in clinical research through peer–peer mentoring approach. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Retrieved September 15, 2024, from https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/programs/intramural/research-innovation-award/2021-awardees/hasni.html

[5] Hawkins, D. S., & Gore, L. (2023). Children's oncology group's 2023 blueprint for research. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 70(S6). https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.30569

[6] Howell, C., & Brooke, B. S. (2024). Quality improvement efforts to address racial and ethnic disparities in patients with peripheral vascular disease and chronic limb-threatening ischemia. JVS-Vascular Insights, 100093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvsvi.2024.100093

[7] University of Leeds. (2024, August 29). Muslims felt excluded from health policies during COVID-19. EurekAlert! Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/1056116

[8] Winn, R., Winkfield, K., & Mitchell, E. (2023). Addressing disparities in cancer care and incorporating precision medicine for minority populations. Journal of the National Medical Association, 115(2), S2-S7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2023.02.001