TekTalk Episode 2: Dr. Burnett

Episode 2 Transcript

Introduction

Yujung: Welcome back to TekTalk! This podcast is produced by Teknos, the TJ science journal team. TekTalk episodes will be released once a month, with each episode featuring recent scientific news and interviews with TJ students and teachers. Today, we will be talking about something we are all familiar with: stress. Specifically, what implications does stress have on the body? What are today’s scientists doing to fix it? What can students do to help? In Science News, we will be talking about research concerning stress and anxiety in mice. This will be followed by an interview with Dr. Burnett, a member of our very own TJ faculty. Dr. Burnett is the teacher of the semester-long courses DNA Science 1 and 2, and one of the two Biotechnology Research Lab directors. Before coming to TJ, she taught as an adjunct professor at Georgetown University and worked on a number of biology-related research projects, primarily on the effect of aging and chronic stress on the risk for cardiovascular diseases. More on her research later.

Science News

Seon Woo: Today’s Science News will be about how obese mice lose anxiety when “zombie cells” exit their brain. Zombie, or senescent, cells are semi-dormant cells that no longer divide and accumulate in a given area of the body, impairing biological functions. Notably, the presence of senescent cells contributes to anxiety in both humans and mice. In order to further examine how senescent cells impact anxiety levels, researchers have studied the behavior of mice in various environments. Anxious mice tend to avoid open areas, move along outside walls, and perform poorly in navigating mazes. Observing these behaviors, the researchers concluded that the anxious mice had significant accumulation of fat and senescent cells in the region of the brain controlling stress.

Interview

Isabelle: Why and how did you decide to go into the field of biology?

Dr. Burnett: Well actually my initial plan was to study chemistry, so I went to college and ended up double majoring in chemistry and biology, because I couldn't decide. I really liked chemistry and I liked being in a lab, but I also wanted to have everything I did be relevant to human health, which is definitely more the bio field, and so I ended up double majoring and both, and when I got to graduate school, I ended up in the chemistry department because biochemistry was part of the chemistry department at the University of Texas, Austin, and so my PhD is actually in chemistry. But the research I did was actually completely biologically related, so I think the main reason why I wanted to do biology was because I wanted to have an impact on human health and wellbeing.

Isabelle: Before you became a teacher, what did you primarily research, and what was the most memorable project you worked on?

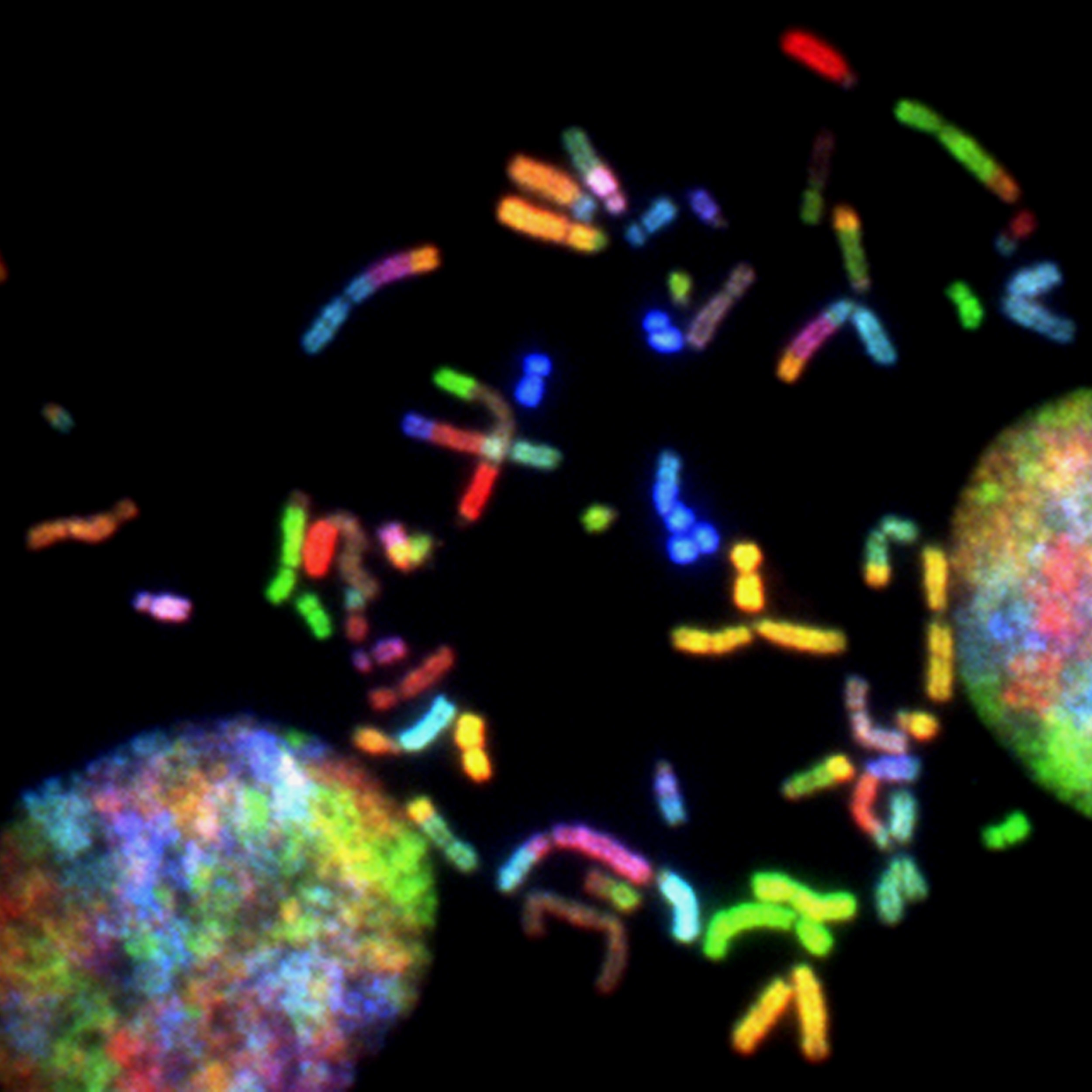

Dr. Burnett: So before coming to TJ I was working for the Medstar Health Research Institute, which is downtown in Washington Hospital Center, and it's part of Medstar Health, so I had a joint adjunct appointment at Georgetown University and I did a lot of work with people over there, but my main field was in cardiovascular disease. I was studying initially the relationship between infection and cardiovascular disease. There was some interesting data that suggested that people had been infected with certain viruses or bacteria during their lifetime that increased their risk of having heart diseases and heart attacks, and so that was initially how I got into the field. But I ended up doing a lot more than just that- we kind of morphed into studying collateral blood vessel development, which is a way of trying to stimulate the growth of new blood vessels to bypass any kind of blockages that may exist. And so we were looking at the role of different types of cells in that process- particularly lymphocytes, macrophages, T-cells, CD4 and CD8-positive T cells, and we were looking at the effect of aging on this process, the effect of stress on the process. Probably my favorite research topic that I was looking at was the effect of chronic stress on cardiovascular disease and vulnerable plaque development, and some of my favorite mentors were studying stress in the context of obesity and metabolic syndrome, and since obesity and cardiovascular disease go hand in hand, it was a natural way for me to join in to what they were doing, and complement their research.

Isabelle: Could you talk a bit more about your projects relating to chronic stress in mice- maybe some of the more interesting stories?

Dr. Burnett: Sure. So I was studying the effect of chronic stress on cardiovascular disease, and we were using a special model of mouse called ApoE-knockout mouse, which has very high levels of cholesterol, and we were stressing them chronically. The type of stress we were using was cold water stress, where the mice had to stand in a centimeter of ice water for an hour a day, for about four weeks. Although that sounds terrible, it's really no different from having to walk across the college campus in the freezing cold in the winter, or standing at the bus stop. It doesn't really hurt the mice, it just gets stressful. So that was the model of stress we were using, and we were looking at the development of Atherosclerosis in their aortic sinuses and in their brachiocephalic arteries, and during this study, we actually were in the process of stressing the mice, we had been stressing them for several weeks, actually. One of my postdocs was working in the lab and came into my office and said 'Dr. Burnett, Dr. Burnett, we have a problem!' and I said, 'Well what happened?' and he said that one of the cages of the mice that we'd been stressing had babies in there. What had happened was when the mice were bred in the animal facility, normally the mice are weaned from their mothers at three weeks of age and you separate the males from the females at that time. Somehow, one of the females had accidentally gotten put into a cage with the males, and that had ended up resulting in an unexpected pregnancy. We didn't realize that was even happening until the babies were there. At that point, I actually got really excited, because I said 'Oh, we should study these mice, because they've been stressed for their entire prenatal development, and I wonder what kind of effect that will have on their cardiovascular disease status'. We let them grow up, and we had to do a control study where we had mothers that weren't stressed, and we studied that little small group of mice to see what kind of interesting results we had, and it was actually very interesting. The mice seemed to have worse atherosclerosis, so I ended up writing an entire NIH grant proposal based on this unexpected result that we had not planned- unplanned pregnancy- and got funded by the NIH to do a more complete study looking at the effects of chronic stress prenatally as well as in adults.

Isabelle: What were some of the challenges you encountered?

Dr. Burnett: Well, research as a whole is always challenging. In general, the rule of thumb that I like to give is that 90% of what you do doesn't work when you do research, and you have to try again and again, and not everything works in the end, but eventually some things do work if you tweak the system and figure out troubleshooting the problems that you're having. I've had all kinds of challenges, from instruments failing and animals dying, or the animal models that we thought we were receiving wasn't actually what we received, to postdocs losing all the samples they had spent four months trying to generate. I've had all sorts of issues, as well as personnel issues in the lab, where there were conflicts between people who were working for me. In fact, I think actually that's probably the biggest challenge. Because research is so difficult and you have to have so much patience to be able to actually be successful at research, it can be kind of depressing. I feel that it's very important to have a positive work environment and to support each other and to have a very team-oriented kind of approach. I learned early on that if you have conflicts in your lab and people who aren't getting along, it just brings everybody down, and the best way to approach the whole process is to create an environment where people want to help each other and work together and celebrate everybody's successes, because even if your experiment isn't working, if you're helping someone else on their experiment and it is working, then you can feel good about that.

Isabelle: So why did you decide to shift away from a research-oriented job and become a teacher here at TJ?

Dr. Burnett: Well, my favorite part of doing research was actually teaching other people, and I had a lot of experience with summer students at my lab, and I had experience with graduate students who were working for me, as well as postdocs and MD fellows who came into the lab. Just being able to teach them how to do an experiment, how to analyze their data, helping them write their papers- that was the most satisfying thing for me. I was excited when I got my adjunct professor appointment at Georgetown because I was hoping it would mean I would have more of an opportunity to teach, but that didn't really turn out the way I was hoping, and so I always kind of felt unfulfilled in that area because I felt like, "Gosh, I'm helping these people in my lab, but there's only like eight of them, and I wish I could be helping more people". When I ended up making the decision to come here, that was kind of something that had been in the back of my mind for a long time. The real reason I came here was because there was a lot of reorganization going on in my institute and I was going to have a new boss, either Boss A or Boss B, and I wasn't really sure that I wanted either one of them for my boss. Funding was getting questionable, my grant was going to be running out soon, and one of my fellows was moving to Miami because her husband had gotten a job there and she'd gotten a postdoc at the University of Miami. Another one was going to do his cardiology fellowship at Tufts, another of my staff was expecting her second child, and so I thought, "wow, I'm going to lose all of my staff, and I'm going to have a new boss who I don't know if I'm going to like working for them or not, and maybe I should look for something else to do." My daughter, actually, was applying to TJ, and so I had gotten on the website to see when they were going to release those letters to tell if you if you had been accepted, and when I did that, I saw this little thing over on the side of the website that said "do you want to teach at TJ?" and I thought "hmm" and I clicked on it, and that's what happened.

Isabelle: Wow! So, what have you learned since becoming a teacher?

Dr. Burnett: Well, I've learned that you can be a scientist, whether you are in a lab full-time or not, because I feel like I'm still doing science everyday, especially with my seniors who are actually doing research. I feel like learning how to teach effectively is a science in in of itself, so I try to do experiments with my students to see how it goes, if they enjoy it, if they learn something, if they get interesting results, and you change things up every year, just like you kind of change things up when you're doing an experiment to keep making things better, making improvements, and I can still do my science, just a little bit differently.

Isabelle: So, can you tell us a little bit more about some of your favorite past senior research projects that you’ve seen in the lab?

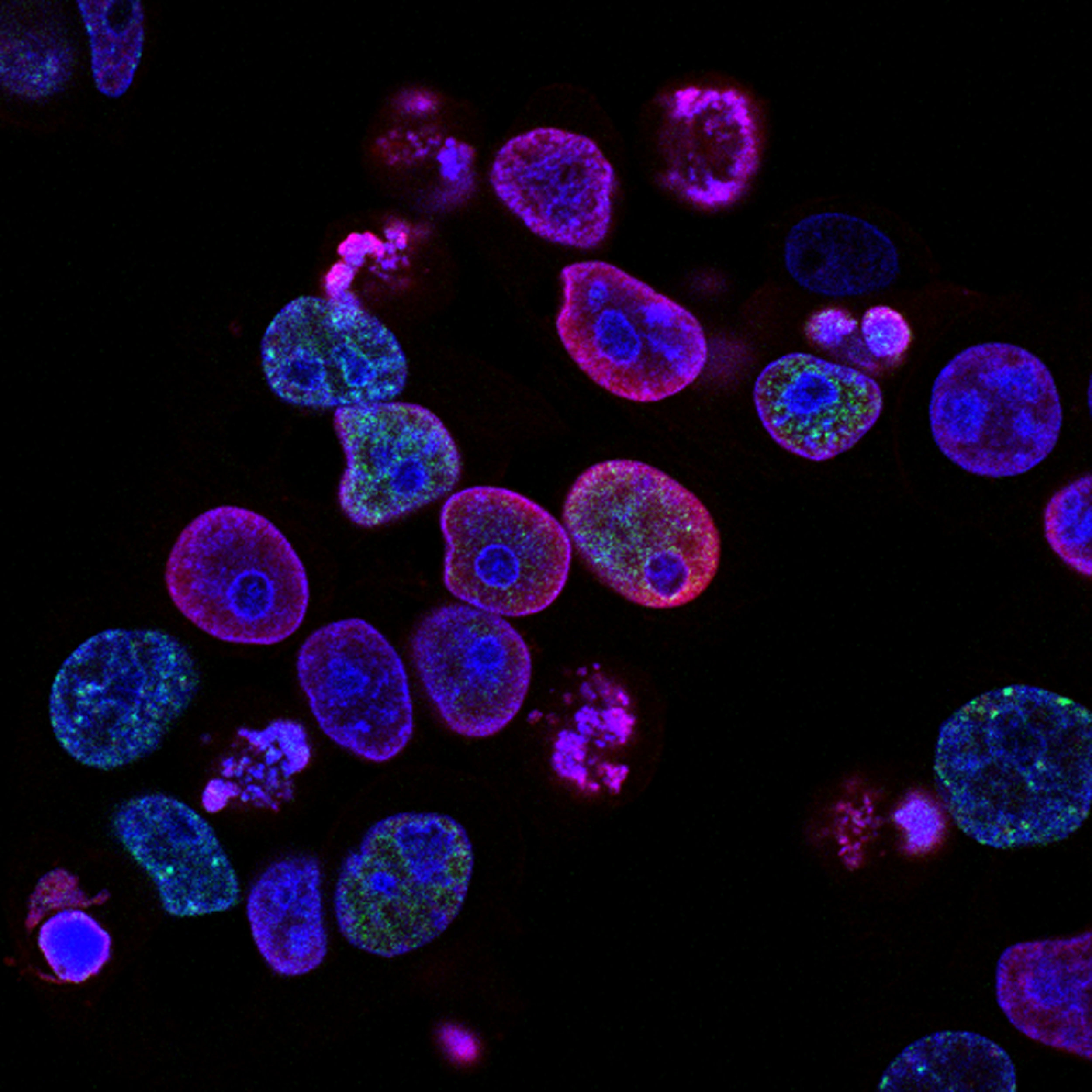

Dr Burnett: Well, some of the projects that we have going on have started a couple of years ago, and one of the ones that stands out for me is a project that began as a collaboration with the National Park Service. There's this black biofilm growing all over the Jefferson Memorial, and actually Mr. Hannum had a connection with someone that he knew that was talking to him about this, because she worked for the National Park Service. He thought "wow that's a really interesting project, I wonder if TJ kids would like to be involved with that", so he sent out an email to all of the staff at TJ to see if anyone was interested, and I guess I was the only one who answered, because I thought "wow that's kinda cool", and I knew that we had this great instrument here, a next generation sequencer that would allow us to identify all the species that were growing on the monument, and so that was how that project began. We've been working on it for three years now, we've gotten some very interesting results that we've shared with the National Park Service, and we've actually moved on to working also at Arlington National Cemetery because they have biofilm problems there. Those problems were a lot of fun because we get to go on field trips to different locations and collect samples, we actually get to work with people from National Park Service and Arlington National Cemetery, I've gotten to present student data at a National Park Service meeting and participate in some brainstorming and planning meetings at Arlington National Cemetery about how to get rid of this biofilm, because none of them want it there, because it's black and makes everything look very dirty. We've gotten to work with collaborators in Milan, Italy and from Temple University who are also studying biofilms, which is pretty cool. We've also been trying to grow our own model biofilms in the lab, which has been interesting and we keep learning things every year about that. That's one of my favorite projects. But I also like the cancer projects that we have going on, we have a lot of cancer cell-lines and students come up with interesting ways that they want to try and treat cancer and I enjoy doing that too.

Isabelle: Cool! So, do you have any advice for students looking to go into the biology-related research? What would you like for your students to take with them as they pursue this kind of research in the future?

Dr. Burnett: Well, I think the thing that I would like people to recognize is know something about yourself. Do you have the patience and the perseverance to go into research? Are you comfortable with failure (laughter) and troubleshooting and trying to do the same thing over and over again until you get it right, because you really have to be committed to that approach when you are doing science? Science is a hard field. There’s a political side, there’s a culture that goes along with doing science, and I think a lot of people don’t recognize that. They kind of have this glorified image of scientists making breakthrough discoveries in a lab, and they don’t realize that in order to get there, you have to have funding that you have to literally fight for (laughter) amongst your peers, and oftentimes that’s very, very difficult to get. It’s difficult to get successful results and get papers published. And it’s not an easy path, but it can be very rewarding and very fulfilling and I think it’s important for people to kind of know what they’re getting into before they head down that path. But I think once you learn the skills of doing science and being tenacious and not giving up on something, and troubleshooting—those are skills that will last forever and can be applied to many other aspects of your life.

Isabelle: Cool! Well, thank you so much for being with us here today for the interview! And we really appreciate the stories and the information you shared!

Dr. Burnett: Sure, no problem! Thank you for asking.

Conclusion

Seon Woo: Thank you for joining us on this week’s podcast! Today, we discussed the biological effects of anxiety and stress in the brains of mice. Our guest was Dr. Mary Burtnett, TJ’s Biotechnology Research lab director, who shared with us her own research on stress and experiences as a teacher. Thank you for listening to our podcast and see you next time on Tek Talk!

Outro

Yujung: You were listening to TekTalk.